Features

Gowanus, Green Infrastructure, and Public Health

Terrapin Bright Green

Share

Learn more about our Phoebe work and services by emailing us at [email protected]. Follow the conversation on twitter: @TerrapinBG | #PhoebeFramework.

This post explores the public health benefits of green infrastructure and uses the Gowanus neighborhood in Brooklyn, NY as an example of how this type of infrastructure can be implemented to benefit communities. During a site visit to Gowanus, three sites were identified to examine the opportunities to develop green infrastructure where people live, work, and play.

By Maggie Rice

Recently, the once separate realms of public health and green infrastructure (GI) — defined by NYC as “an array of practices that use or mimic natural systems to manage urban stormwater runoff” — have begun to commingle to create benefits for communities around the globe.1 Professionals in the fields of public health, architecture, urban planning, and policymaking are coming together to build solutions utilizing the large body of research surrounding nature’s positive impact on human health and wellbeing. In an urban environment, GI offers a way for humans to connect with the natural environment, while providing relief from the public health burdens often associated with living in a city. New construction and redevelopment projects present a canvas of opportunities to incorporate GI into a community’s day-to-day life and impact their health in the places they live, work, and play.

Social factors play a role in an individual’s health. Belonging to a minority ethnicity, earning a low income, and being linguistically isolated are examples of characteristics of populations who are particularly vulnerable to their immediate environment.2 These characteristics of vulnerable populations were taken into consideration when selecting the three sites in Gowanus for GI implementation.

Opportunities in the Gowanus Neighborhood of Brooklyn, NY

Bioswales incorporated into the construction of 365 Bond apartment complex along the Gowanus Canal. Copyright Maggie Rice.

In order to compile the variety of public health benefits obtained from GI into a holistic view, we visited the Gowanus neighborhood in Brooklyn to observe its current GI and speculate on future GI. The Gowanus Canal’s historic industrial activity led to decades of toxic waste accumulation in the canal, resulting in its present-day infamy as an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) registered Superfund site. The planned remediation of the canal has sparked new residential and commercial developments along its banks, many of which embed GI. These developments use GI to decrease the amount of water reaching the area’s combined sewer overflow system, which when overwhelmed contributes to the canal’s pollution. Although the use of permeable GI has recently increased in NYC, Gowanus still remains a heavily industrial area with large amounts of impervious surfaces.

Where We Live

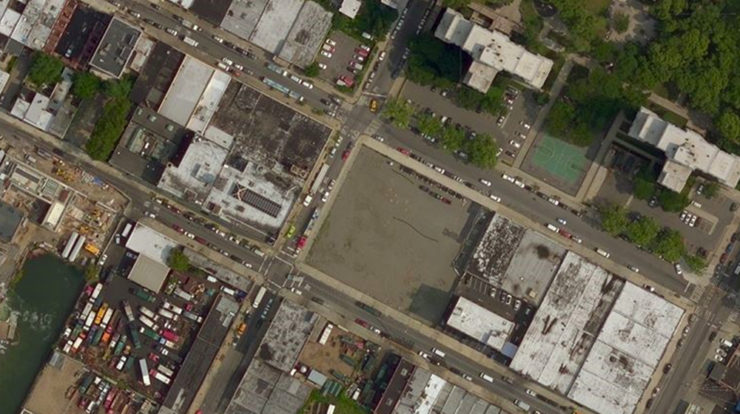

Vacant Lot near NYCHA Residences

The environment in which we live has a crucial role in our health and overall wellbeing. During our site visit, we observed a large, fenced-in, vacant parcel located at the southeast corner of Nevins St. and Baltic St. This site was exemplary for speculating on the opportunity of integrating GI strategies. The parcel is adjacent to four New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) complexes which house over 3,300 residents of low and moderate income. This location serves as a fantastic example of how GI can be incorporated into future developments to mitigate stormwater events and benefit the public health of the surrounding community.

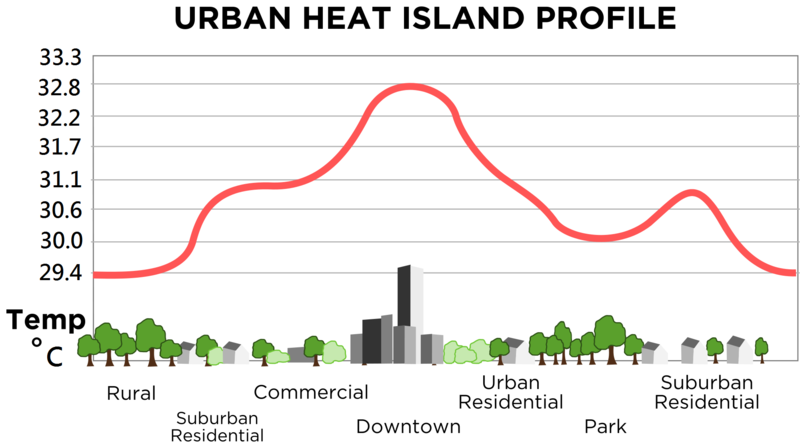

As this site develops, GI such as bioswales and street trees can be added around three sides of the site, while the lot itself can be turned into a small urban forest, providing stormwater management while encouraging environmental stewardship from within Gowanus. These suggested GI upgrades can improve public health by lowering local air and surface temperatures. The lack of trees and large amounts of impervious surfaces in this area of Gowanus may be contributing to the urban heat island (UHI) effect, where the air and surface temperatures of an urban area are much warmer than surrounding rural areas due to heat-absorbing surfaces such as buildings and parking lots.

Profile of the urban heat island effect showing an increase in temperature in non-vegetated areas. Copyright TheNewPhobia/Wikipedia

Vegetated GI such as bioswales, street trees, and urban forests can mitigate hot temperatures during extreme heat events by reducing the amount of impervious surfaces that absorb heat and by providing the cooling effect of evapotranspiration and shade.3 Reducing the UHI effect in a neighborhood can create a microclimate that in turn can lower indoor temperatures and help vulnerable populations avoid the health effects of extreme heat events.

Health effects associated with extreme heat exposure are heat exhaustion, heat stroke, and mortality. Using the NYC Department of Mental Health and Hygiene’s Environment & Health Data Portal, we can see that the area of NYC containing the Gowanus neighborhood has some of the highest rates of heat stress related emergency department visits. One study found that during heat waves there is an increase in emergency department visits for health issues such as acute renal failure, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes, putting those with pre-existing conditions at a greater risk.4

NYCHA requires an application and an additional fee each month for air conditioning units, a cost that many in this population may not be able to afford. A study in NYC found that deaths due to heat waves were less likely for residents living in locations with more green space.5 The addition of bioswales, street trees, and an urban forest will increase the green space near these NYCHA complexes and reduce air temperatures, providing much needed relief from heat-related health outcomes in a location where vulnerable populations live.

Where We Work

Warehouse and Parking Lot on the Canal

Providing almost double the amount of manufacturing and construction jobs than the surrounding area, Gowanus remains a hub for blue-collar employment. This makes locations such as our second site — a warehouse and parking lot located at the northeast corner of Carroll St. and Nevins St. along the Gowanus Canal — an ideal spot to integrate GI for the benefit of worker health. Spending 40 or more hours per week in an industrial setting reflects that where we work plays a crucial role in our overall health and wellbeing.

Supporting local industrial and manufacturing workers with vegetated spaces provides a reprieve that may improve their mental health. Continuous loud noises and many other aspects of industrial work can take a toll on the mental health of employees, leading to higher levels of stress and anxiety in industrial workers compared to the general public.6 The effects of stress on our health can range from an upset stomach to chronic health problems, such as cardiovascular disease and psychological disorders.7 Inverse relationships have been found between neighborhood green space and self-reported stress; levels of the stress hormone cortisol decrease as the prevalence of green space increases.8,9 Even images of natural settings can help to reduce stress and allow individuals to recover faster from mild stress.10 Offering a location with visible vegetated GI, like street trees, bioswales, green roofs, and green walls around a lunch spot may help alleviate some of the stress felt by industrial workers in Gowanus and improve their overall mental health, while also providing stormwater management.

Where We Play

Under The Tracks Playground

Undeveloped area underneath the F/G subway tracks along 10th Street between 2nd and 3rd Avenue. Copyright Maggie Rice.

Where we choose to play and recreate can also have a significant impact on our health. Our third site — an area underneath the F/G line subway tracks on the southeast side of the Gowanus Canal — was once a playground but was closed due to the safety concerns of a deteriorating facade. As the remediation of the tracks comes to a close, this location would be a good location for a new playground that incorporates GI into its design. This new playground could include a turf field, rain and butterfly gardens, permeable pavers, as well as bioswales and street trees similar to the previous site.

Additionally, studies have shown that vegetated spaces such as GI in a playground can improve public health by reducing the rate of childhood obesity in the surrounding population. Estimates show that nearly half of elementary school-aged children are overweight and one in four are obese in NYC, greatly exceeding the national average.11 A study done in Indianapolis found an association between accessible neighborhood green spaces and lower body mass index (BMI) scores in children and youth. Higher access to green space was significantly associated with lower BMI scores as well as lower odds of children’s BMI score increasing over 2 years.12 Increasing the amount of green space, by using GI strategies such as rain and butterfly gardens, trees, and bioswales in the design of the playground, may help in alleviating the burden of childhood obesity in the Gowanus neighborhood.

Why is this important?

Urban areas across the globe struggle with similar environmental and public health concerns, and the resources to address them are often limited. Strategies, such as GI, offer a means of tackling multiple issues at once. In the Gowanus neighborhood, stormwater management provided by street trees, vegetated bioswales, gardens, green roofs, and permeable surfaces can also support populations that may suffer from extreme heat events, mental health issues, and high rates of childhood obesity. Researchers must continue to study and provide evidence on both the environmental and public health benefits gained through GI, providing policymakers with the justification to include GI in future developments. Continued research and increased dialogue between professionals in these overlapping fields can help promote the integration of GI strategies for the benefit of the environment and human health.

Where to go from here?

Green infrastructure can impact our health and wellbeing in a multitude of ways. If you’re interested in learning more about the many ways in which GI can lead to improved public health, please contact our team at Terrapin.

Maggie Rice is currently a Master of Public Health graduate student at Columbia University studying Environmental Health Sciences. She is interested in the public health effects of climate change and how building capacity at a local level through preparedness planning and the built environment can create resilient communities. At Terrapin, Maggie researched ways in which aspects of Phoebe can have public health benefits.

Maggie Rice is currently a Master of Public Health graduate student at Columbia University studying Environmental Health Sciences. She is interested in the public health effects of climate change and how building capacity at a local level through preparedness planning and the built environment can create resilient communities. At Terrapin, Maggie researched ways in which aspects of Phoebe can have public health benefits.

*Feature image copyright Cas Smith. Header image copyright Bing Maps.

References

- “NYC Green Infrastructure Plan: A Sustainable Strategy for Clean Waterways,” PlaNYC and NYC Environmental Protection, Sept. 2010, http://www.nyc.gov/html/dep/pdf/green_infrastructure/NYCGreenInfrastructurePlan_LowRes.pdf.

- Cooley et al., “Social Vulnerability to Climate Change in California,” A White Paper from the California Energy Commission’s California Climate Change Center, July 2012.

- Christopher Coutts, Green Infrastructure and Public Health, Routledge, 2016.

- Knowlton et al., “The 2006 California Heat Wave: Impacts on Hospitalizations and Emergency Department Visits,” Environ Health Perspect, vol. 177, Jan. 2009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1289/ehp.11594.

- Madrigano et al., “A Case-Only Study of Vulnerability to Heat Wave-Related Mortality in New York City (2000-2011),” Environmental Health Perspectives, vol. 123, no. 7, 2015, http://dx.doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1408178.

- Rao S and Ramesh N, “Depression, anxiety and stress levels in industrial workers: A pilot study in Bangalore India, Industrial Psychiatry Journal, vol, 24.1, Jan-Jun 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0972-6748.160927.

- “Stress…At Work,” National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, No. 99-101.

- Roe J and P Aspinall, “The restorative benefits of walking in urban and rural settings in adults with good and poor mental health,” Health & Place, vol 17, 2011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.09.003.

- Ward Thompson et al., “More green space is linked to less stress in deprived communities: Evidence from salivary cortisol patterns,” Landscape and Urban Planning, vol. 105, 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.12.015.

- Brown et al., “Viewing nature scenes positively affects recovery of autonomic function following acute-mental stress,” Environmental Science & Technology, vol. 47, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/es305019p.

- Thorpe et al, “Childhood Obesity in New York City Elementary School Students,” American Journal of Public Health, vol 94, no. 9, Sept. 2004.

- Bell et al., “Neighborhood Greenness and 2-year Changes in Body Mass Index of Children and Youth,” Am J Prev Med. vol. 35, Dec. 2008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.07.006.

Topics

- Environmental Values

- Speaking

- LEED

- Terrapin Team

- Phoebe

- Community Development

- Greenbuild

- Technology

- Biophilic Design Interactive

- Catie Ryan

- Spanish

- Hebrew

- French

- Portuguese

- Publications

- Occupant Comfort

- Materials Science

- Conference

- Psychoacoustics

- Education

- Workshop

- Mass Timber

- Transit

- Carbon Strategy

- connection with natural materials

- interior design

- inspirational hero

- biophilia

- economics of biophilia

- Sustainability

- wood

- case studies

- Systems Integration

- Biophilic Design

- Commercial

- Net Zero

- Resorts & Hospitality

- Energy Utilization

- Water Management

- Corporations and Institutions

- Institutional

- Ecosystem Science

- Green Guidelines

- Profitability

- Climate Resiliency

- Health & Wellbeing

- Indoor Environmental Quality

- Building Performance

- Bioinspired Innovation

- Biodiversity

- Residential

- Master Planning

- Architects and Designers

- Developers and Building Owners

- Governments and NGOs

- Urban Design

- Product Development

- Original Research

- Manufacturing

- Industrial Ecology

- Resource Management

- Sustainability Plans

- Health Care

- Carbon Neutrality