Features

Following the Footprints of Nature – an interview with Dakota Walker

Dakota Walker

Share

This interview was conducted and first published by Sebastian Klemm for his blog “proofing future, bridging people + ideas”. To see the original publication and Sebastian‘s many other interviews and posts, please visit proofingfuture.eu

“It begins with an ethos of responsibility for the whole — to mimic nature’s quest to give back more than it takes. We must accept our role as contributing members of a larger system and allow that ethos to inform our day-to-day decisions,” says Dakota Walker, associate project manager and research analyst at Terrapin Bright Green, where he helps to develop advanced resource use strategies that align the built environment with the natural environment.

What personal encounters & experiences, what “ecosystems” (natural, cultural, educational, international, spiritual), shaped your current personal practice respectively?

My earliest memories of learning about ecosystems involved walking through the forest with my father, listening to him narrating the functions and interactions and themes all around us. It was the first time I understood the forest as a community, a system of relationships with incredibly varied actors. Those were the experiences that endowed me with a respect and sense of responsibility for life in all its many forms. Having since learned some of the scientific backing, the magic I see in nature has only deepened, simply because there is still so much to learn and so many opportunities to improve human systems using nature’s ingenuity.

On the other hand, I have also been exposed to a world in which a person is more likely to experience nature through a screen than in real life. Most people don’t have the personal experiences to internalize a responsibility for the natural environment in which we live. Putting aside judgement, the dominant culture and nature disconnect is simply the framework through which all environmental progress must pass. I think my exposure to an unapologetically profit-seeking economic environment, and an individualistic, convenience-seeking social environment has given me a realism for the tone environmental progress must take.

What is your field of work at Terrapin Bright Green?

Terrapin Bright Green is a research and consulting firm that seeks to address some of the complex obstacles currently facing the built environment with insights from nature. Those insights might come from how nature and its many diverse organisms solve a design challenge (biomimicry), or insights from how we interact with and respond to nature and its sensory and spatial characteristics (biophilia). Our goal is to translate emerging science into actionable knowledge for designers, engineers, corporations, and governments.

My roles as associate project manager and research analyst centers around understanding and employing the many research fields and disciplines that inform building design and operations. That can mean making assessments as to a strategy or technology’s reflection of ecological principles or pushing design teams to explore opportunities to improve health and wellness in buildings based on research of, say, attention restoration theory or psychoacoustics. While in that sense, our projects can range significantly, they are threaded together with a quest to align our building with nature in all its many facets.

What are life’s principles? How can we make them applicable in both our everyday as well as through sustainable design and engineering? What is the ‘secret sauce’, needed to move from a conceptual understanding of life’s principles to real world applications?

At the very basic level, I believe life’s purpose is to organize and create. As Buckminster Fuller says, life is the antientropic counterbalance to the universe’s increasing entropy. Meaning as the universe becomes increasingly random (2nd law of thermodynamics) life acts to create more order. And no species is more successful of an antientropic as humans.

However, what we humans have not yet mastered is the third and often understated imperative, which you might call sustainable destruction or recreation. We have yet to integrate a holistic “regeneration” function into our societal operating system – or more accurately, we have pushed aside that responsibility in the pursuit of ever more growth and creation.

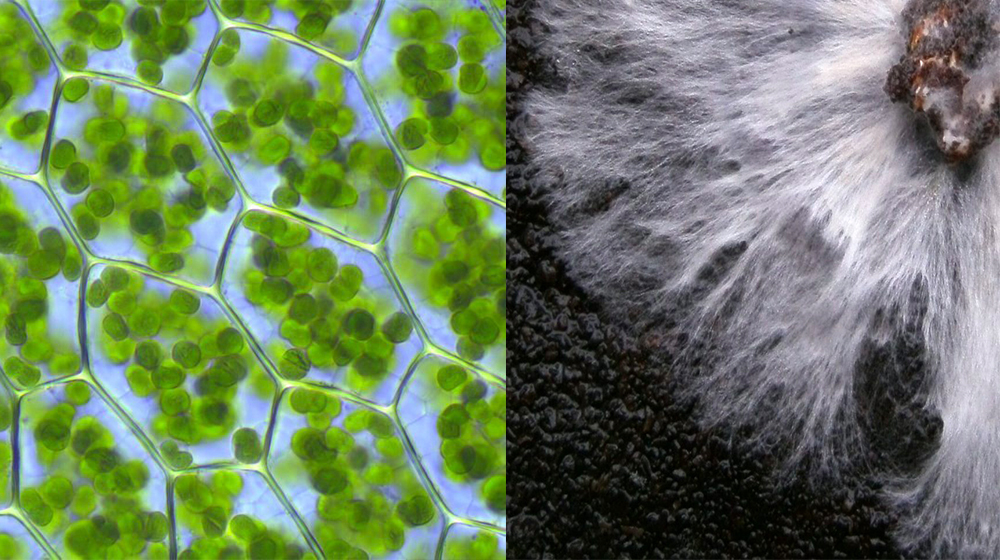

In a sense, half of an ecosystem’s functions are breaking down, assimilating and repurposing resources. An entire section of nature’s processes we consider an externality. Waste. The “secret sauce” is removing the definition of waste from our dictionary and recognizing that there is value in so much of what we currently see as waste. We need to introduce a concept of sustainable destruction (cradle to cradle) and internalize the process of recreation into our models of operation.

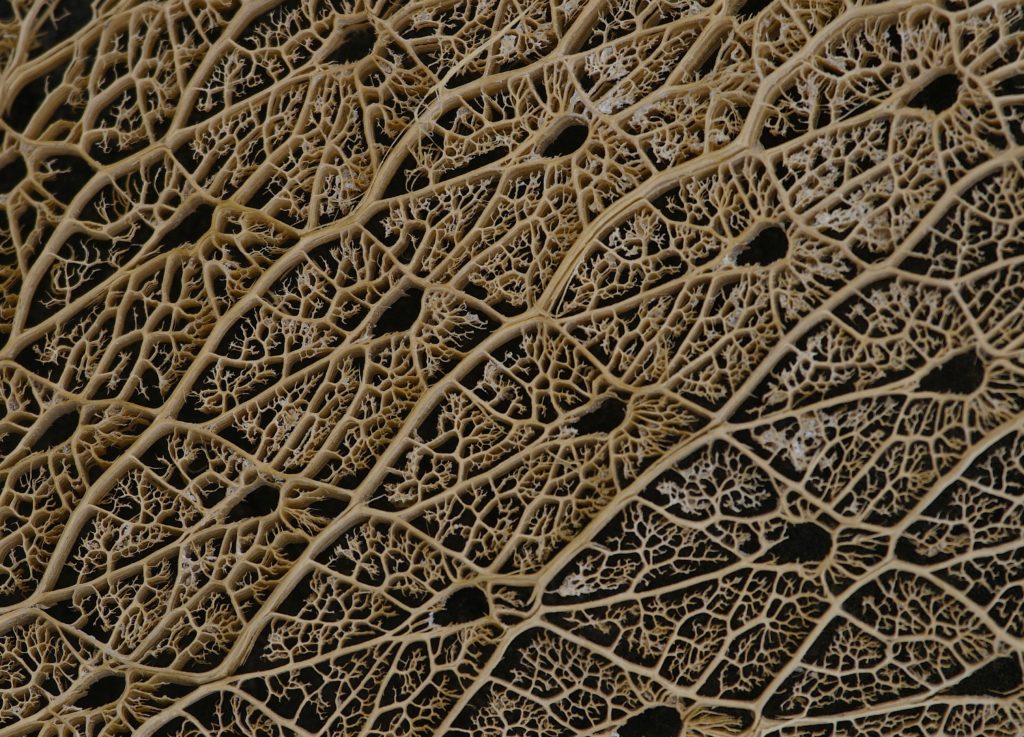

The cycle of life: plant cell organizes, Mycelium breaks down.

© Jay Reimer (left) & Toby Kellner (right)

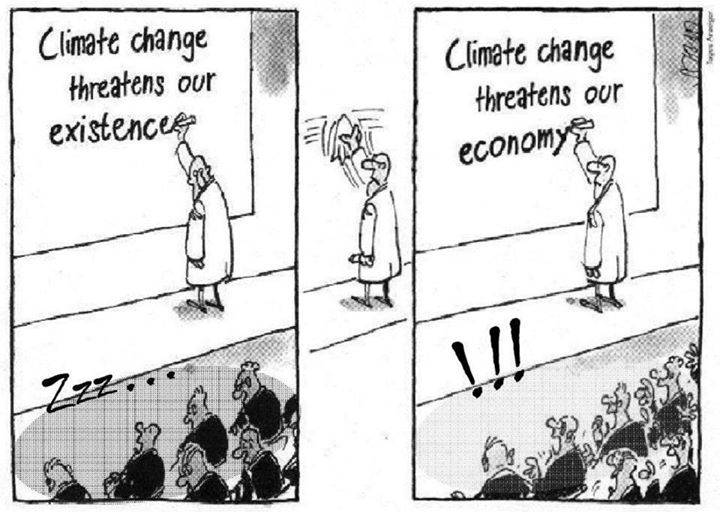

Do environmental- and intergenerational sustainability always have to have a financial incentive to be tackled?

Fundamentally, all living things operate on incentives. The bee doesn’t pollinate out of moral obligation, it simply seeks out nectar. The ingenuity is the system capitalizing on the bee’s desire for nectar to accomplish a function. A function that the bee doesn’t even know it’s carrying out.

Ideally, sustainability should be a bi-product, or an invisible feature of our system of operating. And because money is our nectar, it will ultimately be the means by which we accomplish these background tasks.

What are possible solutions in your point of view: How can biomimicry (innovation inspired by nature) gain traction in the business world?

A successful idea or technology is one that outperforms all other alternatives. Biomimicry allows us to tap into those innovations that have outperformed all other variations for millions of years. That doesn’t just mean high-performance from an “environmental” standpoint. Often, it’s a solution with the least materials inputs, or fastest build times, or most heat resistant, or creates the least drag. In other words, it’s the best option from a business standpoint.

In our publication Tapping into Nature, we explore some recent bio-inspired innovations, both from an environmental performance standpoint and one of profitability.

What is your opinion on putting a price on nature as a service by framing natures´ ecosystem services? In which ways does it help and or hinder us to design for & be eco-effective?

I believe this is an incredibly effective tool to define ecosystem services in the language in which our society operates. You could even say nature puts a price on nature in that if it doesn’t create the most value with the least cost to the system as a whole, it won’t remain. The problem is our definition of value and the way in which we recoup value.

We can put a price on clean air, but that doesn’t mean that those who contribute to cleaning the air can derive value based on that price tag. Clean air is a public good.

The key innovation here would be a system that can materialize ambiguous or long time-frame value into dollar value. This may be where blockchain can augment our current capabilities.

Pushing beyond neutrality: How can companies and factories reimagine themselves as a positive ecosystem and become net-positive facilities?

I think the first step in that direction is to actually understand the surrounding ecosystem and how it operates. Two seemingly similar ecosystems may manage resources and maintain ecological health in vastly different ways. And if we want to contribute positively to that system, we need to learn to mimic the nuances of these ecosystem functions.

One facet of our work at Terrapin Bright Green revolves around quantifying the complex and resilient natural systems in a way that allows it to more easily inform our building practices. One of our ongoing projects is called “Phoebe”, which (phonetically) stands for Framework for Ecology in the Built Environment. This initiative seeks to answer one key question:

How can we recreate the specific ecological functions that were occurring on-site prior to development in the building practices and facility management processes we introduce?

Given that a sustainable world already exists for 3.8 billion years (as the biomimicry movement puts it): Where did we get life’s principles wrong? Which concepts, designs or dogmas may have led us in the wrong direction?

First, it’s worth noting that it’s only in the last century that we have truly grown into our world from both a physical and mental standpoint. The concept of earth as a finite, closed system with a quantifiable carrying capacity was only understood recently in the grand timeline of human existence. Only in the last half millennium do we have the population to truly influence the overall planetary health. Only in the last hundred years did we acquire the information and tools to see the effects of our practices and the decisions we have as a global species.

The problem now stems from how we handle information and approach solutions. We have prioritized specialized knowledge accumulation to such a degree that we don’t have the skills to recognize macro problems effectively nor develop solutions that address a problem holistically. We tend to maximize one variable to the cost of all others.

Now, what effects can Crypto have on how we operate as a society?

Blockchain has tremendous potential to transform our models of operation. While seemingly complex, it’s conceptually a basic enough technology that it can be applied to nearly any facet of our “societal operating system.” And yet it should be noted that these opportunities are for the most part theoretical. There is still much to learn before understanding the full implications of this technology.

One of the more exciting potential of blockchain revolve around its ability to efficiently aggregate small decision, allowing personal intent to have wider impact. It has the potential to provide greater autonomy to individuals seeking to do the right thing and greater oversight on those who aren’t.

In the same way we use governments to regulate public and common goods (among other things), blockchain, along with perhaps a honed artificial intelligence, can be a means of oversight; a spokesperson for the whole, or for future generations, and a way to recognize issues that may not come into view as one individual living for 80 years.

How did your article come about: What inspired you to write about Blockchain in regard of Improving Human Agency in Environmental Decision-making?

We are progressing so fast from a technological standpoint that I believe we are missing opportunities to reflect on their more altruistic potentials. Given the lens that environmentalists necessarily view society (critically), it’s easy to become transfixed by the issues we are creating with each new technological advancement (granted there are MANY).

Without being ignorant to the double-sided sword of technological progress, I believe the environmental movement could stand to benefit from an optimistic viewpoint on the ability of emerging technology to address the issues that affect our world. In the current state of government leadership, it seems much of the progress will need to come from the initiative of individuals and companies. Given that crowd, the main goals are to establish a base environmental literacy and to provoke and challenge innovators or entrepreneurs to compete toward saving our planet.

What I see in blockchain is an improved set of tools for operating society, a set of tools that better aligns with the fundamental principles of biological systems—our only benchmark for how to live sustainably.

Could you elaborate on how you see current incentives to practice sustainability become perverted?

The main emphasis in this quote is our inadequate information to make the right decision. If the only information consumers are given about a product is the price, then the best decision consumers can make is to choose the least expensive option.

If producers don’t have the supply chain information to find their own inefficiencies, then they won’t. And furthermore, if a company does practice sustainability, they become less cost competitive because they are accepting responsibility for costs that we as a society allow other companies to externalize. And without a clear way to justify those added costs (i.e. better product information) companies have a harder time justifying their own pursuit of sustainability outside of moral obligation.

From a more general standpoint, most perverse incentives stem from the way in which we progress as an economy. Economic success is dependent on how much “stuff” people buy or “do.” For the producer there is an incentive to limit durability of a product or render a product obsolete with a new version (e.g. smartphone). For the consumer, there is an incentive to spend frivolously and superficially. Given the choice between fair-trade, organic cotton T-shirt produced locally, and one produced using child labor in Bangladesh, the choice is obvious…neither.

Quoting from your article: “(…) a large part of our role in environmental stewardship centers on purchasing behavior.“

How do you feel about a platform or app that – along your purchase request – suggests producers & traders in the order of their sustainability efforts to guide your purchase decision?

That sounds like a logical complement to the ability to log one’s own purchasing decisions. The key in all of this is a standard to quantify a company’s ranking as sustainable. No sustainability challenges is single faceted. The best approach would likely be one that provides raw data and facts in regard to a company rather than one that ranks according to their subjective hierarchy of goals.

And with respect to “life’s principles“: What may be new kinds of indicators and ways of measuring the success of an economy?

Right now, one of our most accepted indicator of economic success is Gross Domestic Product (GDP) – the goal of which is best summed up as “doing more.”

But it only indirectly reflects our ability to do more efficiently, or “do more and more with less and less.” This idea, also known as ephemeralization (coined by Buckminster Fuller), puts greater emphasis on technological development and thoughtful design solutions that allow us to achieve the same function with less resources.

We may also start to look at indicators of circularity in production and waste management. Perhaps a value for the % of resources that were virgin vs. already in circulation prior.

What incentives could a platform provider for energy trading apply to urge people to install the most sustainable product solutions – in terms of highest efficiency ratio & longevity of the system – thus supporting people who provide the cleanest possible solutions of energy production available on the platform?

You get at an interesting point, which is that the current product sales model has limited incentives for longevity or efficiency. The manufacturer puts R+D into lowering a product’s energy use and the consumer gets the lower energy bill. The manufacturer makes a product that lasts 20 years and now they lose the opportunity to sell that consumer a replacement two years later.

One approach to address this issue would be to change the standard model of ownership – also know as product as a service (PaaS). Instead of selling you an air conditioner, a company sells you the service of cool air. That way, they have all the incentive to cool your home with the least amount of energy and with the longest lasting product (because it’s still the company’s product and the company’s energy bill). Any innovation that lowers the company’s energy or product costs with the same level of cool air will increase their profit margin.

Given that the impact of cities on the natural environment continues to grow, can you give examples of strategies for integrating the urban and the natural environment in a cooperative and sustaining fashion?

First, I would argue that the impact of cities on environments grows only because the population residing in cities grows. Per capita comparison to alternative modes of living (suburban or rural) shows a much smaller environmental footprint for those in cities.

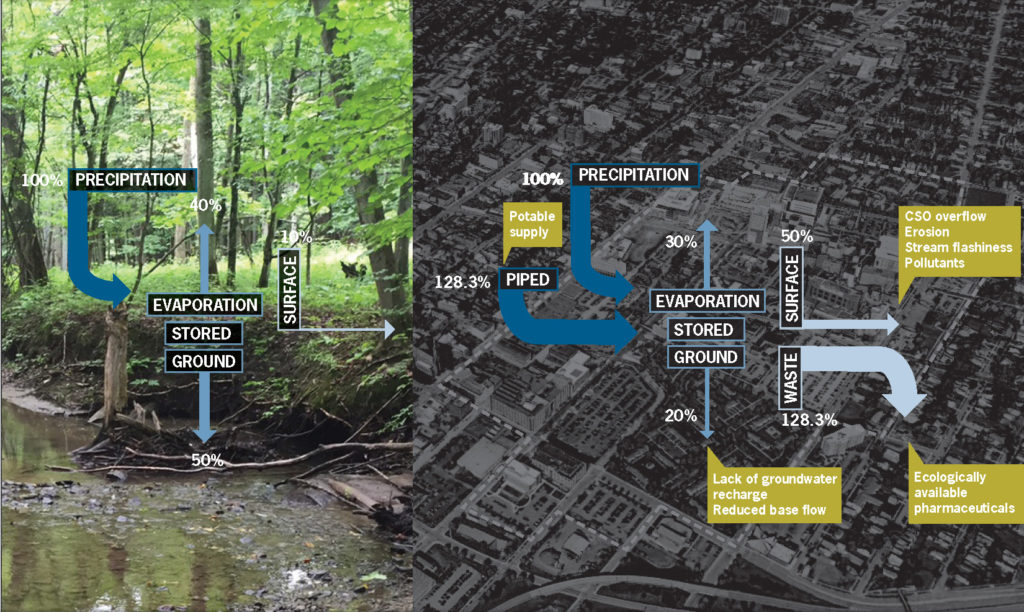

That being said, our current model for city building is still not conducive to life. There is a dichotomy between urban systems and ecosystems. The first step is actually closing the urban system so that those in cities are not actively degrading those natural systems that surrounds it. That alone is a daunting feat given the space constraints and population to sustain.

The next step is to transform the urban environment to be more inclusive of more organisms—dissolve the dichotomy between urban and ecosystems. That means using as much space as possible for habitat whether its rooftop gardens or more street level greenery. It also means making the city more livable by our own species by improving the quality of life and making it more accessible to all of our own species, no matter the income, age, or physical ability.

Beyond climate-neutrality: How can we evolve positive footprints, become eco-efficient in our actions? (eco-efficient meaning: ‘beneficial’ for nature, rather than doing just less bad)

Often overlooked, I think the starting point is knowing what it means to be following the footsteps of nature. Nature doesn’t recycle, it upcycles. Nature doesn’t do less bad, it does more good.

It begins with an ethos of responsibility for the whole — to mimic nature’s quest to give back more than it takes. We must accept our role as contributing members of a larger system and allow that ethos to inform our day-to-day decisions.

Sebastian Klemm, who conducted and originally published this interview, currently works in research and development at the DGNB German Sustainable Building Council. Stemming from a background in architecture and participatory art projects, Sebastian gained experience in conceptual and technical design processes, team-building initiatives and intercultural communications. Both in his professional commitment as well as his personal blog publications he is highly motivated to help shape the circular economy, engage for climate positive impacts and foster social equity everywhere possible.

Header Photo courtesy of Eric Sanderson, Wildlife Conservation Society

Banner Photo courtesy of Faye Cornish/Unsplash

Dakota Walker

Dakota Walker is an Associate Project Manager & Research Analyst at Terrapin Bright Green. He recently graduated summa cum laude from the University of North Carolina Asheville with a degree in Environmental Management and Policy. Dakota believes the genius of nature has yet to be matched by human innovation. He’s interested in finding new approaches to solving contemporary policy and design challenges that reflect the resilience and resourcefulness of natural systems.

Topics

- Occupant Comfort

- Materials Science

- Speaking

- LEED

- Terrapin Team

- Phoebe

- Community Development

- Greenbuild

- Technology

- Biophilic Design Interactive

- Catie Ryan

- Spanish

- Hebrew

- French

- Portuguese

- Publications

- Carbon Neutrality

- Environmental Values

- Conference

- Psychoacoustics

- Education

- Workshop

- Mass Timber

- Transit

- Carbon Strategy

- connection with natural materials

- interior design

- inspirational hero

- biophilia

- economics of biophilia

- Sustainability

- Systems Integration

- Biophilic Design

- Commercial

- Net Zero

- Resorts & Hospitality

- Energy Utilization

- Water Management

- Corporations and Institutions

- Institutional

- Ecosystem Science

- Green Guidelines

- Profitability

- Climate Resiliency

- Health & Wellbeing

- Indoor Environmental Quality

- Building Performance

- Bioinspired Innovation

- Biodiversity

- Residential

- Master Planning

- Architects and Designers

- Developers and Building Owners

- Governments and NGOs

- Urban Design

- Product Development

- Original Research

- Manufacturing

- Industrial Ecology

- Resource Management

- Sustainability Plans

- Health Care