Features

The Journey of Sustainability

Bill Browning

Share

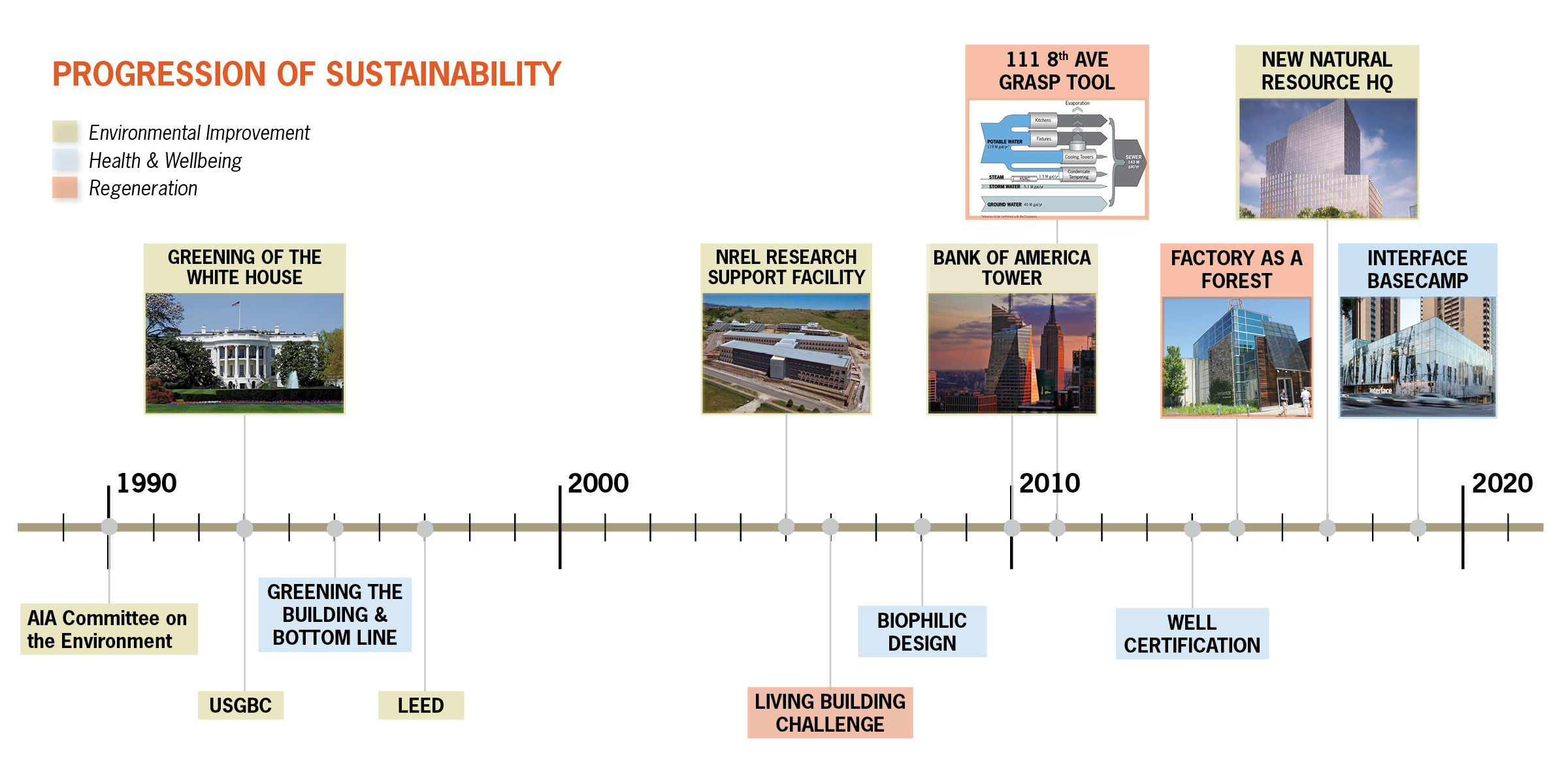

The green building movement and arguably the larger discussion about sustainability have progressed in scope and understanding over the last three decades. Terrapin staff have been at the heart of this journey. In retrospect, this progression can be understood as three distinct levels of sustainability, each with their own focus, and with direct and indirect benefits that help to paint a picture of local, regional, global and industry priorities and trends.

Lowered Environmental Impacts

The coalescing of concerns about energy efficiency, indoor air quality and building construction impacts led to the formation of the AIA Committee on the Environment in 1990 and three years later the US Green Building Council. The mindset was focused on reducing harm to the environment. Rating systems such as LEED, BREEAM, and Green Star were developed as a way to validate environmental performance improvements. The scope and stringency of these systems has increased over the years and the broad adoption of these systems worldwide has had a profound impact on the commercial real estate industry.

This approach to project sustainability focuses on energy efficiency, water efficiency, renewable energy, indoor air quality, material sourcing, stormwater, site habitat and other environmental strategies. Examples of Terrapin’s contribution at this level of sustainability include the Jones Beach Energy & Nature Center, the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco (LEED Platinum), and Merdeka PNB-118, a megatall tower in Kuala Lumpur (LEED Platinum anticipated).

For more on high performance environmental design, see Terrapin’s other features and posts:

- Natural Ventilation: Learning From The Past – by Bill Browning

- Blockchain: Improving Human Agency in Environmental Decision-making – by Dakota Walker

- Transparency in Business: Shedding Light on New Standards in Sustainability – by Rebecca Macies

- From Forest to Faucet: The Importance of Water Conservation – by Rebecca Macies

The topical entry points for sustainability in the built environment have grown over the last 3 decades to include diverse priorities and performance outcomes, from energy and water efficiencies; to materials toxicity and sourcing, IAQ, and the microbiome; to biophilia and equitable access; to bioinspired design and ecological entanglement.

Health and Well-being

The next stage of thinking began with the realization that while the focus of green building strategies leads to significantly reduced environmental impact and improved conditions for the occupants, it might be possible to concurrently focus on the health and well-being of the occupants. This approach looks at avoiding toxins and at providing high quality air, light, drinking water and food offerings, and has inspired certification systems including Fitwel and WELL.

Offices around the world, like this one in Quito, Ecuador, have adopted healthy workplace design from attractive stairways, to daylighting and quality views, to using natural materials. Photo by Lauramoyaarq/Pixabay

From thinking about buildings as human habitat, and how to create conditions most supportive of productivity and well-being, came the desire to reconnect people to experiences of nature in the built environment; biophilia. Biophilic Design is a form of evidence-based design that draws on neuroscience, environmental psychology, and various sub-fields such as visual preference studies, alliesthesia, and psychoacoustics, to create spaces that measurably reduce stress, improve cognitive performance and enhance perception, mood and emotion. This approach encourages design teams to prioritize design interventions that optimize the environmental experience according to space and user type, as well as project goals. Examples of Terrapin’s work in biophilic design include Google’s biophilic design framework, the WELL certified headquarters of Interface Base Camp and the American Society of Interior Designers (ASID), the Westin GEN-5 hotel guest room prototype, the PDX Airport Terminal Core Redevelopment in Portland, OR, and Clif Bar’s industrial bakery in Twin Falls, ID.

For more on health and well-being, see Terrapin’s other features and posts:

- Biophilic Design, More Than Just Plants! – by Bill Browning

- Forest Bathing and the Larger Implications of Accessible Nature – by Julia Kane Africa

- Designing for a Moving Target: Ensuring Human Health in a Changing Climate – by Chris Garvin

Regeneration

Getting to net-zero is an important goal, however just putting a stop to carbon emissions in the atmosphere, or effluents in waterways, does not undo the existing damage to the environment. This type of thinking, which has inspired building standards like Living Building Challenge and the 2030 Initiative, rests on the realization that reducing environmental impacts are in the long run insufficient. This level of sustainability is evolving to encompass emerging priorities in health equity, environmental justice and community vitality, as well as urban planning considerations beyond the confines of a building’s walls.

Consideration is emerging for how buildings and communities function in and contribute to the local site and regional ecosystem. ParkRoyal on Pickering in Singapore. Photo by Engin Akyurt/Pixabay

This highest tier of sustainability focuses on recreating the services that healthy ecosystems provide, such as storing carbon, cleaning water, cycling nutrients, maintaining biodiversity and doing it in a way that supports equity and the dignity of people. This approach also enables a property or community to adapt to climate change and be resilient in the face of public health crises and geophysical events. This is regenerative design. Terrapin’s approach asks what the intact ecosystem of a development site would be doing, and then determines site-specific performance metrics for the design and long-term operation of the building or campus. This strategy includes both ecological and social engagement with/by the local community. Examples of these aspirational efforts are sustainability tools for Google’s 111 Eighth Avenue in New York City, Interface’s Factory as a Forest effort, and Buffalo Niagara Riverkeeper’s Blue Economy Framework.

For more on regenerative design and resilience, see Terrapin’s other features and posts:

- Another Dimension of Resilience – by Bill Browning

- Embracing the Ecological Perspective – by Allison Bernett

- Advancing Urban Sustainability – by Chris Starkey

- Overview of Terrapin’s services on regenerative design

These approaches form a cumulative progression—a regenerative strategy includes both environmental performance improvement and health and well-being. Ultimately, though a project team could choose to engage at any of these levels to create buildings that are better than conventional performance, the regenerative approach holds the greatest hope for achieving holistic and long-term benefits for people, their community and the ecosystem.

Topics

- Environmental Values

- Speaking

- LEED

- Terrapin Team

- Phoebe

- Community Development

- Greenbuild

- Technology

- Biophilic Design Interactive

- Catie Ryan

- Spanish

- Hebrew

- French

- Portuguese

- Publications

- Occupant Comfort

- Materials Science

- Conference

- Psychoacoustics

- Education

- Workshop

- Mass Timber

- Transit

- Carbon Strategy

- connection with natural materials

- interior design

- inspirational hero

- biophilia

- economics of biophilia

- Sustainability

- wood

- case studies

- Systems Integration

- Biophilic Design

- Commercial

- Net Zero

- Resorts & Hospitality

- Energy Utilization

- Water Management

- Corporations and Institutions

- Institutional

- Ecosystem Science

- Green Guidelines

- Profitability

- Climate Resiliency

- Health & Wellbeing

- Indoor Environmental Quality

- Building Performance

- Bioinspired Innovation

- Biodiversity

- Residential

- Master Planning

- Architects and Designers

- Developers and Building Owners

- Governments and NGOs

- Urban Design

- Product Development

- Original Research

- Manufacturing

- Industrial Ecology

- Resource Management

- Sustainability Plans

- Health Care

- Carbon Neutrality